A team of Washington University scientists is working on a “one-size-fits-all” approach to help prevent hearing loss and a variety of neurological and neurodegenerative disorders.

Many sensory and neurological disorders are caused by the over-activation of neurons by the neurotransmitter glutamate. Compounds that can block the various classes of glutamate receptors are well known to researchers, but the clinical side effects of systemic glutamate receptor blockade are intolerable due to the widespread use of glutamate by the central nervous system. WashU auditory neurophysiologist Mark Rutherford, PhD, may have found a solution to this dilemma.

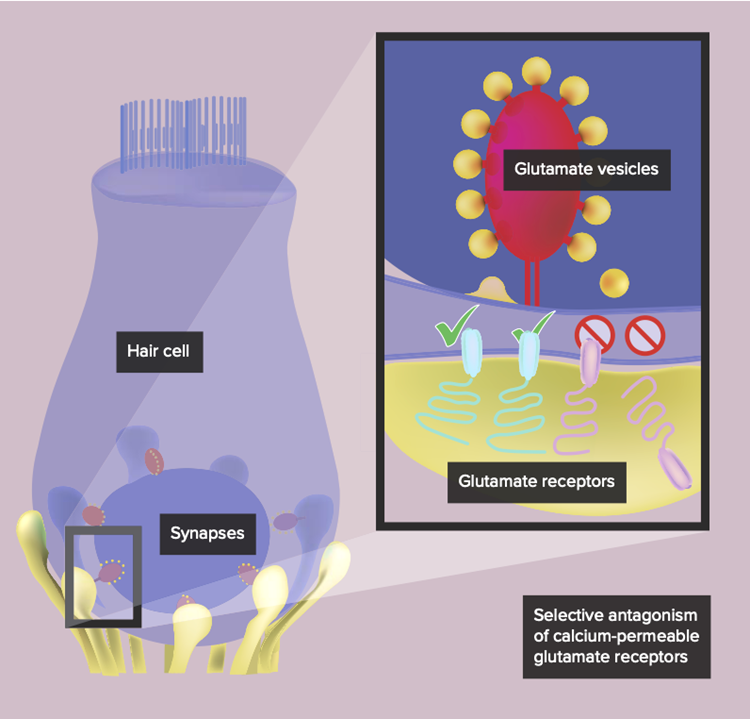

Rutherford and collaborator Stephen Green, PhD, at University of Iowa, discovered there were actually two varieties of one subtype of glutamate receptor – called AMPA receptors – present at the synapses between inner ear sensory hair cells and auditory neurons. One type is permeable to calcium ions – the other type is not. Blocking the calcium-permeable subtype reduced the stress of acoustic injury sufficient enough to protect auditory neurons while still allowing the animals to hear normally.

This type of injury was described in 1969 by Washington University Professor of Psychiatry John Olney, MD, who referenced the term ‘excitotoxicity’ to refer to the mechanism of damage. Today, excitotoxicity is thought to be involved in cancers, spinal cord injury, stroke, epilepsy, traumatic brain injury, hearing loss, and a number of neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Parkinson’s disease.

While the test compound initially used proved the approach could be successful, identifying the best compound for the job will take time and considerable effort. Rutherford has partnered with Roland Dolle, PhD, in WashU’s Center for Drug Discovery for assistance with compound design and synthesis.

Recent pilot studies suggest the approach can be applied to a variety of neurological disorders and stroke, in addition to hearing loss and tinnitus. Early results from trials of brain ischemia in rodents have demonstrated protection with a single dose. However, Rutherford is careful to note that because the receptor targets in the ear and the central nervous system are slightly different, the final therapeutic compounds will be chosen specifically for each application. They will be named Otogard for the ear and Neurogard for the brain.

James Huettner, PhD, in the Department of Cell Biology and Physiology helped to develop the cell-based screening methods useful for early detection of promising compounds. Collaborations with Jin-Moo Li, MD, PhD, and Terrance Kummer, MD, PhD, in the Department of Neurology at WashU will help determine the efficacy of this approach in animal models of stroke and traumatic brain injury.

Rutherford is excited about the potential therapeutic applications of the finding.

“This is a new type of drug for a receptor that has not been targeted in humans before,” he said. “These receptors are implicated in many diseases, so, once our compound is approved for anything, doctors will want to try prescribing it for many things. The key is to avoid side effects by employing very selective pharmacology.”

To date, the team has designed, synthesized, and tested just over 100 compounds in cell-based screens. The next step is to choose a promising few to test in live models of hearing loss, tinnitus, stroke, and epilepsy. Following that, formal toxicology tests will be conducted.

To help facilitate progress, the team is working with WashU’s Office of Technology Management and hopes to create a new company focused on the continued development and refinement of these therapeutic compounds. They are currently seeking outside investment or partnership.

For more information or to inquire about investing or giving to this effort, please contact Mark Rutherford.