The COVID-19 pandemic has had a greater impact on minority populations than others. Unfortunately, health disparities like this are not uncommon. Assistant Professor of Otolaryngology Angela Mazul, PhD, hopes to better understand why these disparities exist and how they can be resolved.

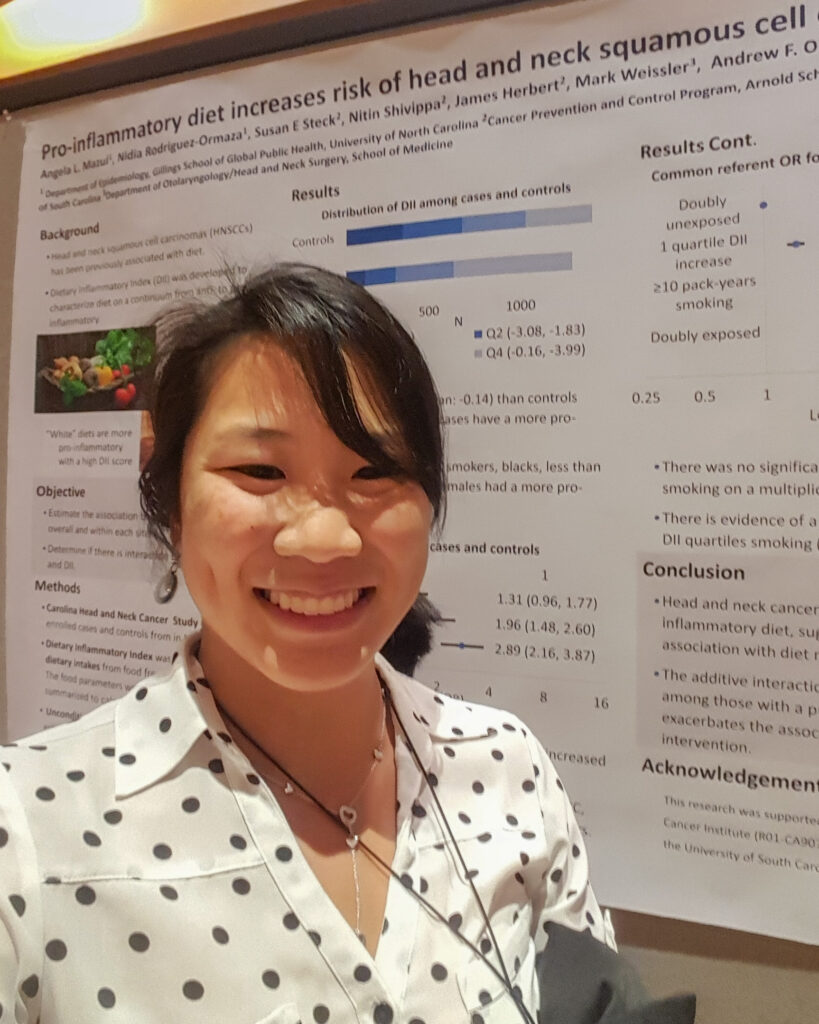

Dr. Mazul’s research is focused on health disparities in head and neck cancer patients. She wants to understand how race, gender, and neighborhood can affect cancer health outcomes.

“Race is socially determined,” she explained. “It has no biologic basis and is not modifiable. To eliminate disparities, we must determine the root causes.”

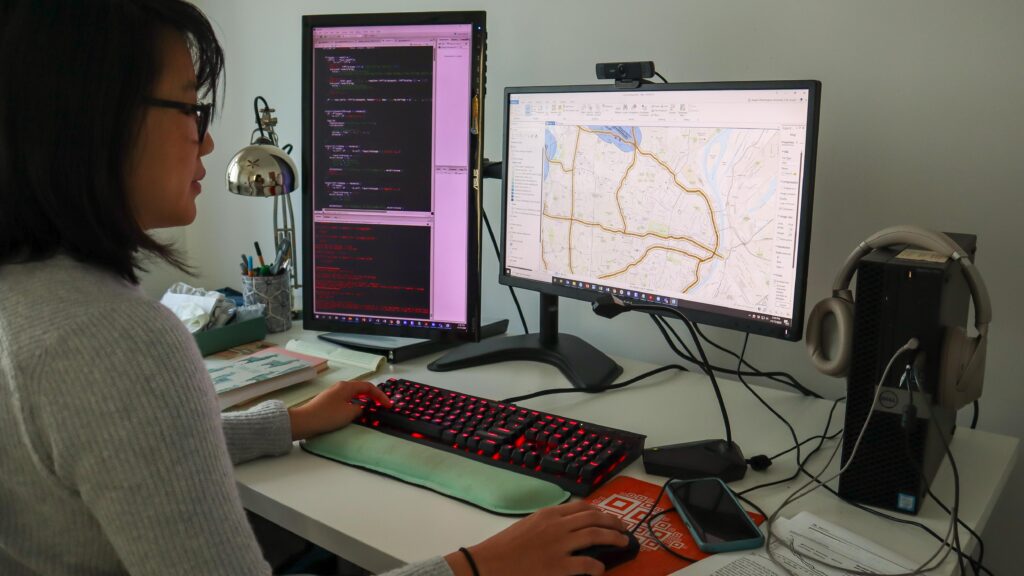

To that end, she is currently working to understand how someone’s neighborhood can affect cancer outcomes, such as stage at diagnosis, recurrence, and survival. Most of her studies use existing data, including data from cancer registries such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) and Siteman Cancer Center to map a cancer patient’s neighborhood.

“We can link to census data and determine neighborhood characteristics such as socioeconomic status and rural-urban context with this data,” said Dr. Mazul. “Additionally, with location data we can map the distance patients need to travel to obtain care and their adherence to the standard of care.”

Since these studies look at many different factors, large sample sizes are needed to study these effects. To obtain a large sample size, most data are retrospective. That means most of these data were not collected to determine the underlying causes of health disparities and do not necessarily contain the specific data needed to answer our research question. Progress however is being made.

Dr. Mazul has been studying current trends in disparities by race and found that females have better survival than men in HPV-negative head and neck cancers, especially among Black Americans. However, among HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers, Black women have the worst survival. Additionally, although oropharyngeal cancer rates are decreasing among Hispanic and Black men, the burden of cancer overall is increasing since these populations are increasing and aging. She has also found an interaction between race and rural-urban context where rural Black patients have worse survival than white rural patients. The next steps are to expand on these findings by looking at the interaction between neighborhood and race.

According to Dr. Mazul, what’s missing is key data on the personal experiences of the patients and their barriers to care. Once they determine neighborhoods that potentially have high cancer rates and high diagnoses or mortality stages, they can conduct qualitative studies to determine why these neighborhoods have such poor cancer outcomes.

“I am hoping the results of these studies will determine neighborhoods or populations for intervention,” she explains. “If specific populations are non-adherent to treatment, then determining the underlying cause, such as access to reliable transportation, could lead to interventions that make a measurable difference.”

Dr. Mazul credits their current progress to a strong team of investigators. Collaborators on these studies include head and neck surgeon Jose Zevallos, MD, MPH, and many members of his lab: Ricardo Ramirez, MD, Ben Wahle, MD, and research technician Sophie Gerndt – and the many medical students who have helped, including Emily Yan, Jacob Clarke, Smrithi Chidambaram, and Erik Nakken.

Dr. Mazul has also been working with Sid Puram, MD, PhD, and Sean Massa, MD, on clinical epidemiology and disparities projects. She recognizes the fine mentorship of Dr. Graham Colditz in the Division of Public Health Sciences for helpful guidance. Looking ahead, Dr. Mazul is interested in studying the interaction between social determinants of health and genomic biomarkers, especially as precision medicine for cancer treatment becomes more readily available. To learn more about her research please contact Angela Mazul.