A board member for the Central Institute for the Deaf, James Seeser, PhD, is a champion, volunteer and donor supporting the Department of Otolaryngology and the Newborn Hearing Screening Program in Missouri and at the national level.

Where does your passion for supporting diagnosis and treatments for hearing loss come from?

I am a CODA (child of deaf adult). Many years ago, my father asked me to become involved with helping deaf people. However, this is something that I didn’t act on until I retired. I saw firsthand the difficulties experienced by deaf people in a hearing-speaking world. In addition, I also saw how the low competence in English, common among ASL [American Sign Language] communicators, hindered their ability to independently participate in many activities not requiring speech or listening.

All of this motivated me to use whatever skills and money I have to help ameliorate the condition of Deaf or Hard of Hearing (DHOH) people. This is done primarily through early diagnosis and intervention.

What inspired you to become a board member for the Central Institute for the Deaf?

I wanted to learn more about helping deaf children become more highly functioning in a hearing-speaking world. The CID seemed to be at the forefront of this effort.

Why is supporting the advancement of newborn infant screening important? How might this change a child’s life?

Medical science teaches us that the brain’s basic language and communication aptitudes are developed in the first years of life through negative neural selection mediated by the child’s environment. If a child is not exposed to sounds and words very early, then the brain development needed to allow the baby to efficiently do this is hindered and even eliminated. This development process is mostly complete by age two or three.

It is important to start early so that the child can hear the thousands, if not millions, of words that is necessary for full English language development. Languages learned after this point are acquired and used differently by the brain.

If a child has learned ASL as a first language, then different neuronal development occurs. If medical intervention (hearing aids, implants) is not started early, then the probability that the child can reach full hearing/listening potential is diminished. As a CODA who learned ASL first, it is apparent to me that I don’t process spoken language in the same way as a native “listener.”

Started in 2000, the Newborn Hearing Screening program can identify deaf and hard of hearing babies within a few weeks. Early intervention is started within a few months, rather than a few years, as was the case previously.

Some argue that it makes no difference what comes first: ASL or spoken English. ASL is different from English, so an ASL child must learn English as a second language. Many, like my parents, learn and use English at perhaps an elementary school proficiency.

In my more recent volunteer work in the St. Louis Public schools, I saw how primary students quite proficient in ASL struggled mightily with simple English grammar and vocabulary. These people are at a disadvantage to English speakers or writers when it comes to competition in the job market or participation social interactions.

Getting started early is fundamental to a child’s likelihood of becoming an independent, fully contributing and participating member of society. I am fully behind approaches that provides to capable babies the interventions and education allowing them to function independently in society.

Approximately 6,000 babies in the U.S. are diagnosed annually with hearing loss. Most of these babies will not have access to the interventions available in the St. Louis area that allow them the option to fully function in a hearing, English-speaking society.

My vision is that the various entities – CID, Program for Audiology and Communication Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis Children’s Hospital, and other organizations – will find better ways to coordinate and cooperate so that the benefit of the whole is far more than the sum of their parts. For example, one result could be using innovations in both medical and audiological treatment and devices combined with the education of parents, teachers and students to better serve these children.

Having said all this, I realize that there are exceptions to what I say. For those unable to participate in listening and spoken language development, ASL generally becomes the preferred means of communication. Society should make this handicap as small of a barrier as possible. Similarly, greater cooperation among these organizations could also help find innovations in speech to text and enhanced ways for voiceless people to communicate with hearing and speaking people.

Why do you trust that WashU and CID can make a difference for children and people with hearing loss?

They provide key steps in this process; including medical diagnosis and treatment, speech and language therapy, and education. They are critical parts of the “deaf and hard of hearing” intervention system.

Is there anything else that you would like to add?

There is a French saying, “One should learn to flower wherever God plants you.” Fortunately for me, St. Louis is fertile soil as it is arguably among the top locations of research, diagnosis, treatment, and education of children with hearing loss.

I am very thankful for these people and their organizations for allowing me to participate, if modestly, in their activities. The organizations include CID, PACS, the Department of Otolaryngology at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis Children’s Hospital Audiology, Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services (DHSS).

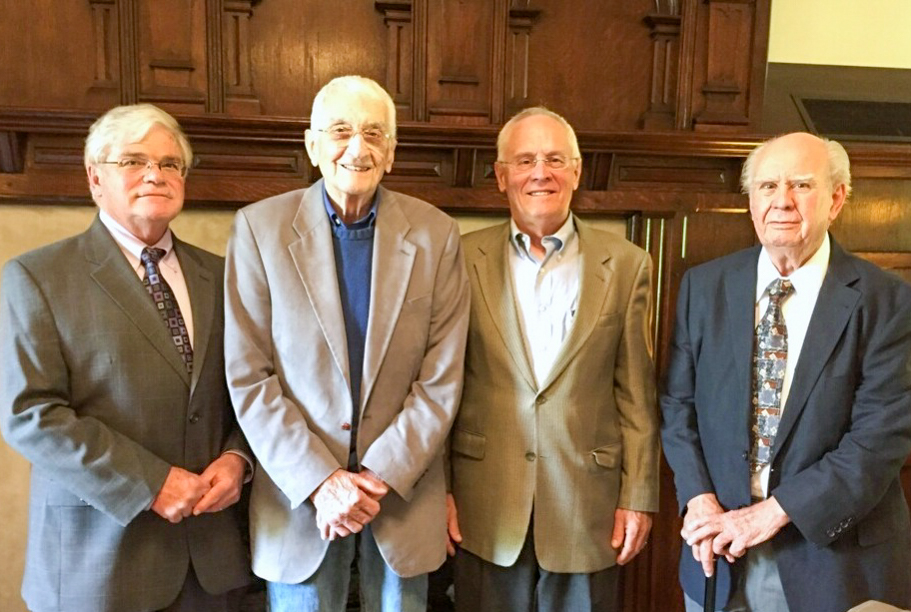

Many individuals have been instrumental in this; including Dr. Craig Buchman, Dr. William Clark, Robin Feder, Dr. Cole, Dr. Jerry Cox and audiologist Jamie Cadieux. At the state and national levels, I am indebted to Catherine Harbison and Kay Park, past chair of the NBHS review committee. At the CDC, I am indebted to Suhana Ema and Marcus Gaffney. I am also deeply indebted to Dr. Marie Richter, a graduate of PACS, for her advice and support.