Understanding the cellular and molecular responses that underlie cochlear implant-induced fibrosis (scar tissue) and neo-ossification (new bone formation) has been hampered by the lack of a suitable animal model for research.

Cochlear implantation provides enhanced hearing for thousands of hearing-impaired Americans each year. And, with expanded criteria allowing health insurance to cover severe hearing loss in one ear along with expanded Medicare coverage, cochlear implants will now be available to more patients.

As with any implanted medical device, the body may react to the presence of the foreign material, causing inflammation, fibrosis and bone remodeling. In fact, post-mortem studies have demonstrated that these reactions are common in cochlear implant recipients.

A mouse model for post-implant changes

The mouse is highly valued for in vivo animal research due to the ability to manipulate its genes. Eliminating or enhancing gene expression can help researchers identify gene products or proteins that are important for cellular responses to events like cochlear implantation. However, performing a cochlear implant in a mouse must be difficult due to its small size.

According to Washington University pediatric otolaryngologist and researcher Keiko Hirose, MD, mouse implantation is straightforward for those who have performed mouse ear surgery for other indications, like endocochlear potential measurements or inner ear fluid sampling. The creation of the CI [cochlear implant] electrode for mice does require special manufacturing. Hirose’s team has been fortunate to collaborate with Roland Hessler of cochlear implant manufacturer MedEl, which fabricates the devices for their use.

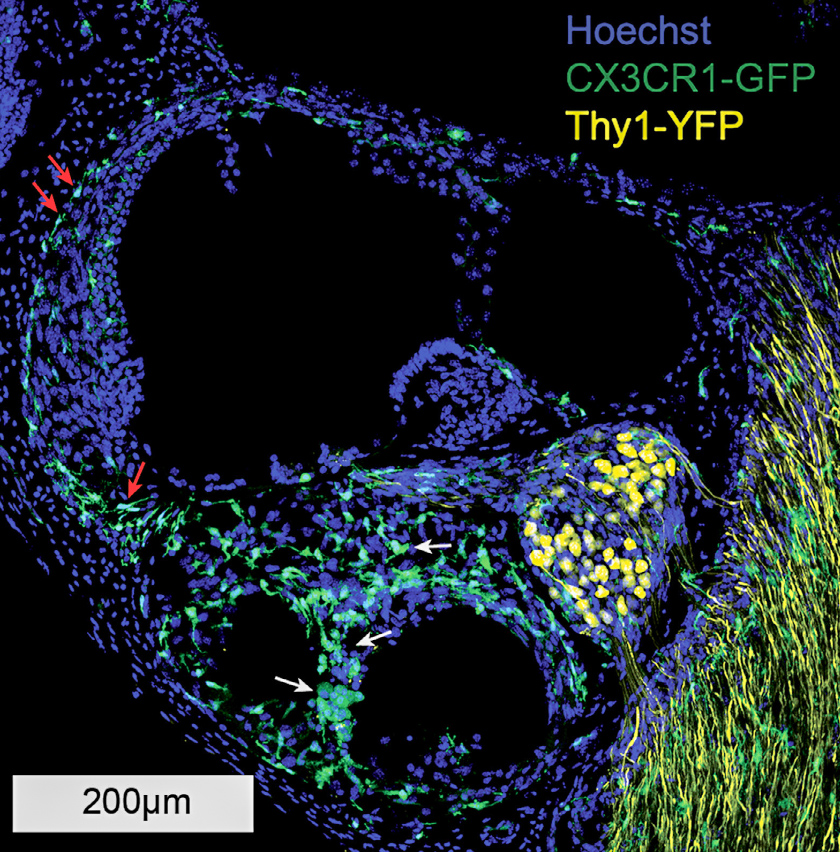

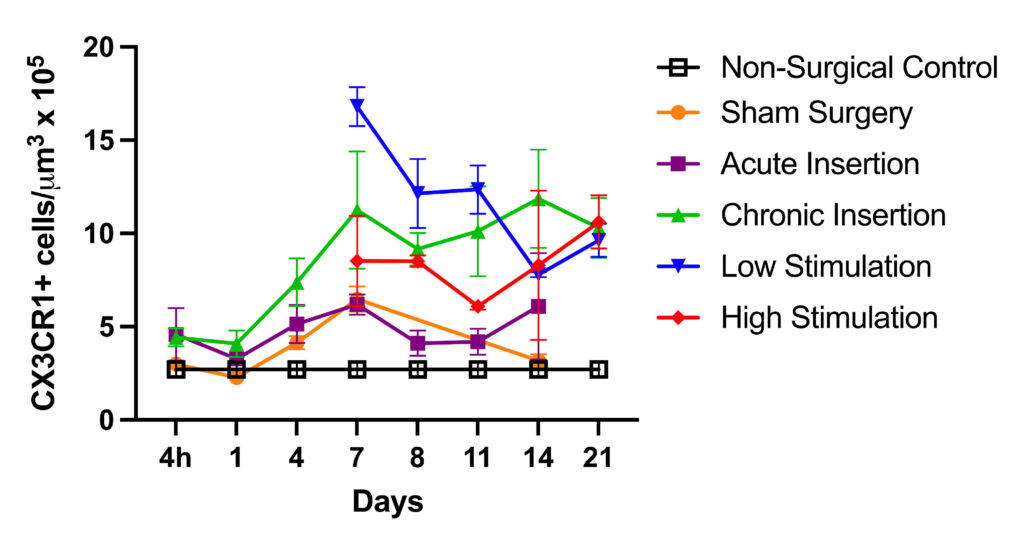

Using this model, Hirose in collaboration with Marlan Hansen, MD, and his team at the University of Iowa has shown a cochlear inflammatory response is present with chronic implantation, even in the absence of electrical stimulation. Genetically engineered mice that demonstrate fluorescent macrophages allow inflammatory cells and neurons to be labeled and easily identified in cochlear specimens.

A lesser immune response was generated by surgery without implantation. Further, fibrosis was evident only in the chronically implanted mice, suggesting that prolonged cochlear inflammation and fibrosis are largely dependent on the presence of the implant, rather than surgery alone or electrical stimulation.

Hirose hopes continued study will allow the development of mitigation strategies for the foreign body response and inflammation, allowing better outcomes for cochlear implant patients.

Next steps

The team is waiting for more implants so they can assess the effect of macrophage depletion on cochlear inflammation, fibrosis and remodeling of the inner ear following chronic implantation and electrical stimulation.

“We have genetically engineered mice that allow depletion of macrophages at the time of implantation,” said Hirose. “It will be a relatively straightforward study to see how the cochlea responds differently in the absence of macrophages.”

There is also a lot to be learned about how the cochlea and auditory system respond to electrical stimulation. Hirose also hopes to use this mouse model of CI eventually to study properties of the spiral ganglion neurons and how they differ in their response to electrical stimulation compared to acoustic stimuli.

Hirose attributes important contributions of this research program to Hansen and Robert Shepherd, PhD, of the Bionics Institute at University of Melbourne, Australia. Both serve as co-principal investigators in this work. The work is supported by the National Institutes of Health through R01 DC018488.

For more information on these studies please contact Keiko Hirose, MD. The full manuscript can be viewed here.