More than 48 million Americans suffer some degree of hearing loss. As the average age of our population increases, so will that statistic. Excessive noise exposure is considered a leading cause of hearing loss, and no FDA-approved treatment is available to prevent noise-induced damage. Scientists working at Washington University School of Medicine may soon change that.

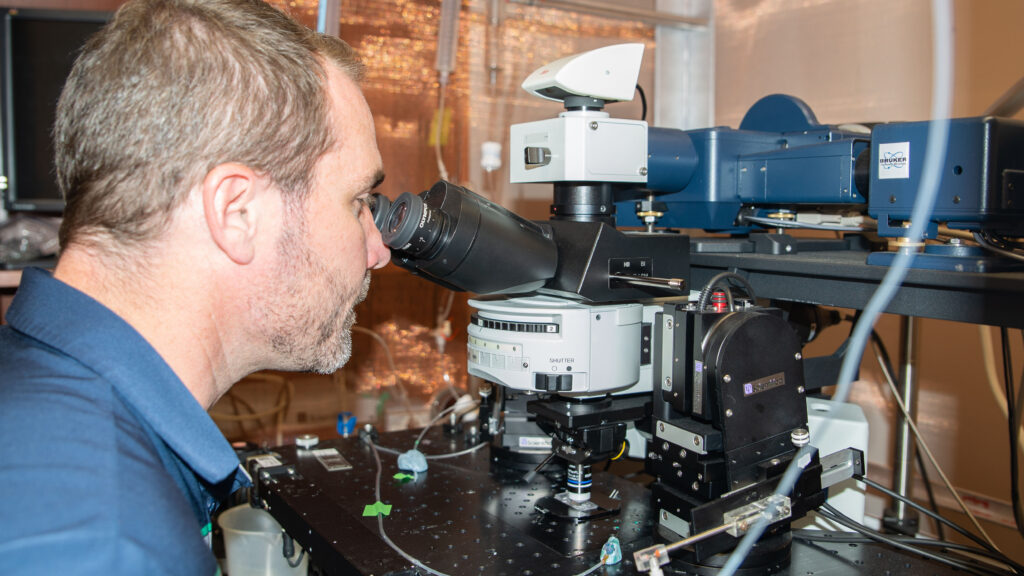

Assistant Professor of Otolaryngology Mark Rutherford, PhD, has been studying the synaptic biology of hearing for several years, focusing on the role of the neurotransmitter, glutamate, used by receptor hair cells in the cochlea to transmit sound stimuli to the brain.

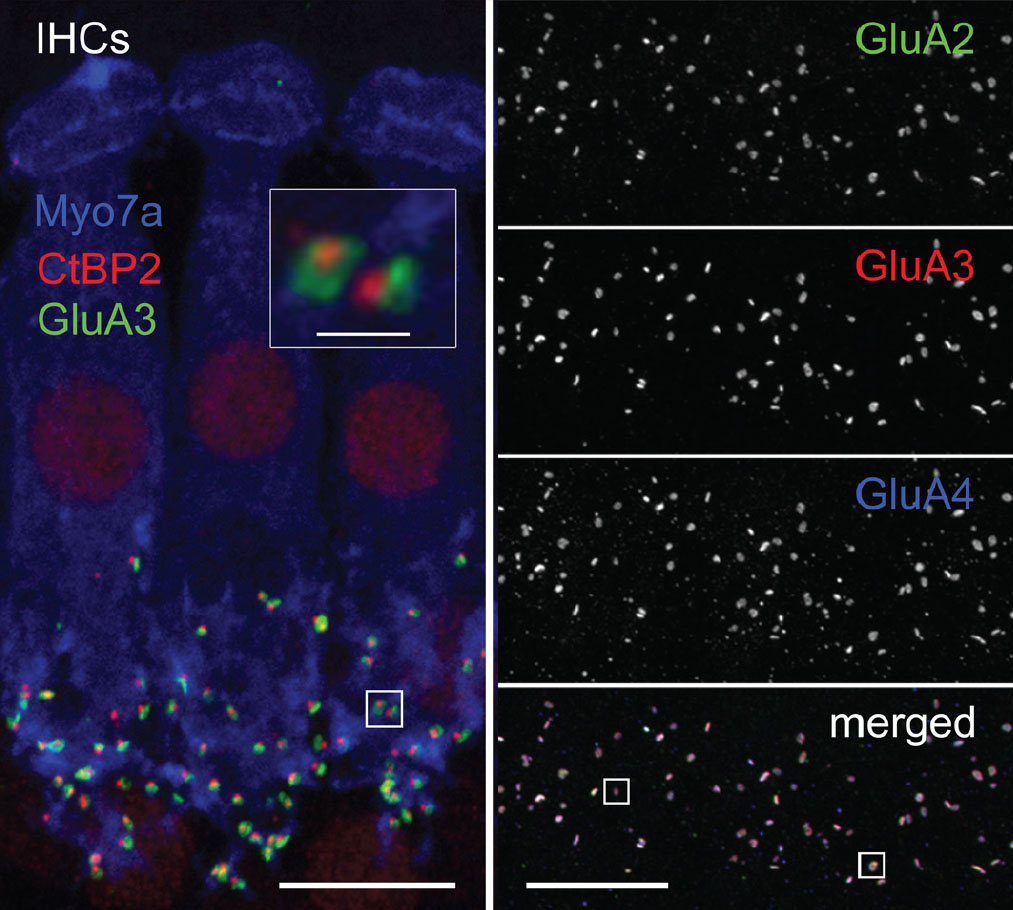

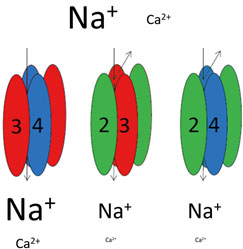

Glutamate is the most common excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, and a number of different glutamate receptors are utilized by neurons to achieve stimulation by glutamate. AMPA receptors represent one class of glutamate receptors known to mediate signaling between hair cells and auditory neurons.

Glutamate signaling is essential for normal hearing, but excessive glutamate receptor stimulation –such as that due to chronic noise exposure – can cause damage to auditory neurons, including damage to the synapses that modulate nerve signal transmission. Pharmacologic blockade of glutamate receptors, specifically AMPA-type glutamate receptors, reliably prevents noise damage to cochlear synapses, but blocking all of the AMPA receptors would also block auditory sensation. In fact, systemic blockade of all AMPA receptors would have widespread and drastic side effects in the central nervous system.

Can we prevent noise damage without blocking hearing?

Rutherford, in collaboration with Steven Green, PhD, at University of Iowa, found that AMPA receptors in the auditory system were not all the same. Some allowed calcium ions to flow into the cell and some did not. In the first demonstration of its kind, they were able to alleviate noise-induced hearing loss in mice by specifically blocking calcium-permeable AMPA receptors while normal activity at calcium-impermeable receptors was sufficient to allow normal hearing to be sustained.

Read more about the team’s early efforts »

NIH award promotes continued effort

Rutherford was recently awarded a $2.3 million NIH grant to continue this work. Specific goals of the new project include:

- Determine the precise molecular anatomy and physiology of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors in the cochlea;

- Determine if post-exposure blockade of the receptor can effectively prevent noise-induced hearing loss for unplanned exposures;

- Determine if AMPA receptor blockade combined with antioxidant therapy can improve the effectiveness of this strategy, especially in models of more extreme noise damage.

Can more effective drugs be developed?

Another focus of the effort has been to optimize the pharmacology available, or to ensure they were using the most potent and specific receptor antagonist possible. The team – including Roland Dolle, PhD, chemistry director of the Center for Drug Discovery at WashU; Jim Huettner, PhD, professor of Cell Biology and Physiology; and Otolaryngology resident, Amit Walia, MD, – developed and tested ten derivatives to measure their ability to selectively block calcium-permeable AMPA receptors. These novel compounds are now being used in further studies.

Can other disorders be treated this way?

According to Rutherford, one of the most exciting prospects of this work is its general application to other nervous system disorders such as tinnitus, stroke, and epilepsy. Pilot studies are currently underway.

“Many nervous system disorders might benefit from selective glutamate receptor antagonism, and this provides us important additional opportunities to test the therapy in the clinic,” says Rutherford. “Currently, only one, broad-spectrum, AMPA receptor antagonist has FDA approval, for use in severe epilepsy patients that do not respond to other treatments. Unfortunately, the behavioral side effects of this treatment can be rather severe. By targeting one subtype of AMPA receptor, perhaps we can reduce or eliminate those side effects and still provide some clinical efficacy.”

To learn more about this work, contact Mark Rutherford, PhD.